Virtual School External Communication

by Mark Sivy

This is a continuing report of a recent research study’s findings.

Effective unambiguous external communication is essential to the operation of a virtual school. Recent research indicates that for virtual school leaders, the means of external communication are more conventional than for internal communication (see previous post) and usually involve email exchanges or phone conversations. The leaders also engage in a variety of face-to-face external interactions including one-on-one conversations, private group meetings, and public events. The findings associated with this topic have been categorized as general external communication, guardian communication, post-secondary education communication, school district communication, vendor communication, representing the virtual school, feedback and input, and marketing.

General External Communications

Even though internal staff receive training and mentoring to engage in intentional and meaningful communications, the individuals who are outside of the school do not. This means that special attention must be given by leaders to ensure proper perception of both outgoing and incoming messages.

Prepared leaders have communication plans and staff responsibilities in place for the schools’ external communications. This includes planning regularly scheduled communications as well as making preparations for unscheduled communications in cases such as virtual school related news, service disruptions, and emergencies.

Guardian communications

Given the diversity of students who attend virtual schools, it’s helpful in addressing the needs of the learners if leaders ensure communication and collaboration with parents (Belair, 2012; Garland, 2011). Communication with guardians is often intended to provide one-way sharing of information. Some leaders receive responses from these broadcasts that are either questions or expressions of appreciation. Two-way individual communication usually resulted from guardians having some concern about a student’s performance, a course, or an instructor.

Some issues with communications resulted from the guardians having too many options for communication. The first task was for them to determine with whom they were to communicate, whether it be someone at the home school, the virtual school instructor, or some other virtual school staff member. The next challenge was for the guardian to determine how to communicate with these individuals. This was usually either via email or phone, which often required the guardian to locate an email address or phone number. The school leader’s task was to have these processes streamlined as much as possible.

Some issues with communications resulted from the guardians having too many options for communication. The first task was for them to determine with whom they were to communicate, whether it be someone at the home school, the virtual school instructor, or some other virtual school staff member. The next challenge was for the guardian to determine how to communicate with these individuals. This was usually either via email or phone, which often required the guardian to locate an email address or phone number. The school leader’s task was to have these processes streamlined as much as possible.

Post-secondary education communications

As the virtual schools expand their offerings and advantages, some leaders have started to communicate and form partnerships with colleges, universities, and technical schools. Typically this is to arrange courses to be delivered with the purpose of offering dual credit.

School district communications

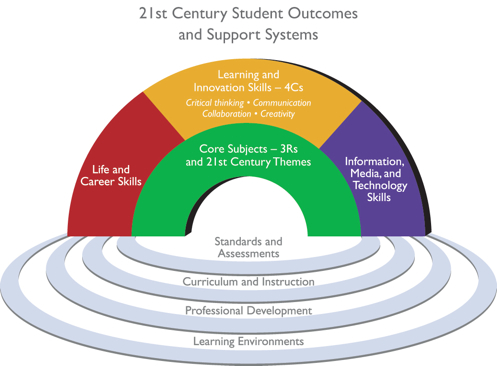

This was the most common form of external communication that was discussed by the participants. As the leaders moved forward with the growth and acceptance of their schools, the student’s physical home school districts seemed to be the best venue to establish a virtual school’s brand and to gain virtual school champions. Depending upon the purpose, these communications were either with the home school (teachers, counselors, principals, or other assigned contact persons) or district offices (district coordinators, superintendents, etc.). These communications ranged from regular updates and announcements to being conversations about specific topics such as ensuring the local schools that the virtual school courses were aligned to standards. Depending upon the purpose or message, these virtual school leaders either communicate directly with the home districts or had a staff member make contact. The leaders typically are personally involved in communications with higher level school district representatives such as school principals or district office administrators.

Vendor communications

The leaders of some schools, typically the ones with smaller enrollments, deal more frequently with vendors. In the larger schools the leader has less frequent dealings with vendors, either because the leader has staff to perform the needed school services in-house or staff who communicated with the vendors. The leader’s role in vendor communications is to ensure that the virtual school provided the most reliable services they could afford.

Representing the virtual school

Virtual school leaders are involved in an assortment of meetings, conferences, committees, and other gatherings external to their schools. Depending upon the function, these could include their peers, vendors, media, government officials, school district administrators, special interest groups, and persons with an interest or stake in virtual schools. During some of these events, leaders find themselves educating participants on the nuances of a virtual school. At other events, the leaders contribute to peer conversations, leveraged the expertise that was present, and advocated for their schools.

Feedback and input

Virtual school leaders use outward facing surveys, assessments, and evaluations for the purpose of enhancing their schools’ operations and offerings. The data are acquired from different sources, such as parents, home school districts, and advisory groups. The tactics included random emails, public forums, annual school surveys, and receiving input from advisory groups. The general sense from leaders is that response rates are lower than they preferred and that they sought ways to improve this.

Marketing

Marketing

To a certain extent, virtual schools are a business that must promote themselves to remain sustainable. Each of the leaders presented an ongoing concern for the acceptance and growth of their schools. Getting the messages out extended from simple word of mouth to having marketing representatives who traveled a state. Their efforts involved branding their school, advertising school offerings, maintaining a positive public image, making press releases, and pushing out communications. Brand recognition takes time to develop but it serves as an important tool in the marketing of a school (Berridge, Henry, Jackson, & Turney, 2009).

The amount of marketing is in large part determined by operational guidelines and the missions of the virtual school. Those schools whose charter limited their scope or that received sufficient funding were less involved in certain aspects of marketing than those that had a broader scope and a greater latitude in determining their own operations, or were seeking additional sources of funding.

Reflection Point – ““The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place.” ~George Bernard Shaw

References

Belair, M. (2012). The investigations of virtual school communications. Tech Trends, August, 26-33.

Berridge, D, Henry, L., Jackson, S., and Truney, D. (2009). Looking after and learning: Evaluation of the virtual school head pilot.

Garland, V. (2011). Leading an Online School. S. Huffman, S. Albritton, B. Wilmes, & W. Rickman (Eds.), Cases on Building Quality Distance Delivery Programs: Strategies and Experiences (pp.109-121). doi: 10.4018/978-1-60960-111-9.